Cinema camera predictions for 2022: what’s the next big thing?

Over the past few years, the digital camera industry has experienced a real boom. Thanks to competition between major players, professional image capture tools have become much more affordable. It seems hard to make he wrong choice buying a camera today for more than $2.5–3K. In terms of image quality and malleability, we have reached such a level that only a specialist can tell the difference between a $90,000 and $6,000 camera. And even then — only pixel peeping at controlled test shots. As a result, camera models and brands now compete mostly in additional functionality, ergonomics and product ecosystem. At the highest level, of course, not much has changed — ARRI still reigns supreme.

Here are some of the key trends we witnessed in recent years:

Full frame went mainstream, with Alexa Mini LF now being the de facto standard for high-end productions;

The hottest, most contested price brackets were $3,500 and $6,000 with 4K 10-bit 422 now being the expected norm for image quality;

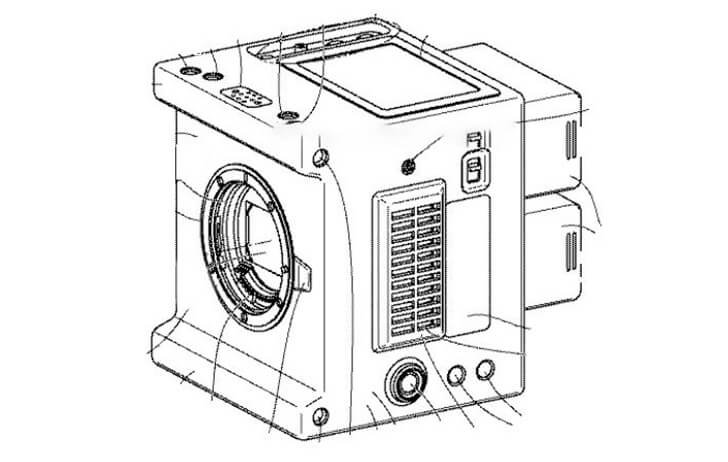

RED’s “cube” form factor gained a lot of traction, particularly with the Chinese manufacturers;

The $6,000 cameras cannibalized a lot of the $10K offerings and the $15–30K bracket went almost completely extinct.

At SHAGRAL video production we were lucky to perfectly time our upgrade and went with the Sony FX6 as the main workhorse. I am extremely pleased with the choice both as an operator and as an entrepreneur (with the exception of a couple of bizarre decisions by Sony). For the next couple of years, the camera issue is settled for us.

But as a true fan of digital imaging technology, I can’t help thinking what to expect next from the camera industry. Some of these points are my wishes rather than predictions, but others are perfectly logical extrapolations of current trends.

I invite you to muse with me below.

Cinema cameras with BSI stacked sensors will be released

In terms of innovation on the sensor front, the main surprises in 2022 should be expected from Canon and ARRI. Let’s start with the latter; ARRI has been teasing a brand new sensor for years now (as a reminder, over the past 10 years all iterations of Alexa have been built around the same ALEV III sensor in various configurations). So far, all we know is that it’s a 4K Super35 sensor with “exciting image quality improvements”. Certain guesses about these improvements may appear if you look closer at Canon.

ARRI’s next Super35 4K camera is said to be mostly in the same form-factor as Mini LF. Same EVF and Codex drives were also confirmed by the manufacturer.

It’s been rumored for a long time that the Canon Cinema EOS line is up for a major update. I’m referring to the new line of cinema cameras with BSI Stacked sensors with DGO. We know for sure (thanks to patent filings) that Canon is hard at work on such sensors. In terms of new cameras that means C300S (S35 8K@60p 16 stops), C500S (FF 8K@60p 17+ stops), and the dynamic range monster C700DR (FF 4K@240p 20 stops) are all rumored to be in the works. It wouldn’t be a big logical leap to assume that the more secretive Sony has something similar in the oven too. After all, we have Sony to thank for most of the breakthroughs in digital imaging technology.

I’m willing to bet that the new Arri Super35 4K camera will be armed with a custom BSI Stacked sensor, and as for DGO, the Germans invented it in the first place. In practical terms, this will mean a significant increase in the dynamic range (perhaps up to or even beyond the limits of human vision) or high frame rates (up to 1,000 fps). Unlikely both at the same time, since the capabilities of such cameras will be limited by the processor and thermal budget.

RAW video won’t become the norm until 2028

You can guess from my choice of camera that RAW is not a priority for my work. Competently shot 10-bit LOG footage is only slightly inferior to RAW in terms of gradeability, but greatly surpasses it in terms of practicality. That said, if there was a decent way to shoot RAW, I would not refuse it. And by “decent” I mean namely: 1) compressed, 2) 16-bit and 3) internal. And there is only one such RAW format today — and it’s REDCODE RAW “thanks” to RED’s aggressive patent policy. We are talking, of course, about a patent for recording compressed RAW video, which other manufacturers are forced to put up with. Every other RAW format is heavily compromised in one way or another to not infringe on RED’s patent.

Only Nikon, with their new flagship Z9, which now writes compressed proprietary N-RAW to the card, has somehow inexplicably escaped the wrath of RED. Whether they will continue to get away with it remains to be seen. But anyway, Nikon is a total outsider in the video/cinema market, what they do or don’t do has little to no consequence.

I will not be surprised to see headlines such as “Nikon removes RAW options from Z9” in the coming months.

So up until 2028, when the patent expires, there are three strategies for productions that need RAW. The first is to shoot on RED, if budgets allow and there is no allergy towards the brand. The second is to shoot on Blackmagic and put up with the shortcomings of the system for the sake of a truncated, but convenient 12-bit “almost RAW”. The third strategy is to take a chill pill and soberly analyze your need or want for RAW (a topic for a separate blog, perhaps).

Cameras will be limited by processors

A digital camera is essentially a computer attached to a sensor. We have already talked about the sensor: the sensors of tomorrow are ready to dish out much more data than the current DSP (digital signal processor) can handle. It is clear that the next revolution must take place in the processor department. A DSP has to perform a lot of tasks in real time, and there’s about to be even more.

DSPs will of course get faster to handle higher resolutions and frame rates. How much faster they can get without exceeding the camera’s thermal budget is unclear. We already see two processors in some cameras: for example, in the A7SIII and FX6 there are two Bionz XR processors that share two sets of tasks — one for processing the signal and writing it to a file, and the second, parallel — for real-time calculations such as autofocus, stabilization, EVF image, lens corrections etc.

Very soon, another set of tasks related to computational imaging may be added, and at some point the DSPs, however many, as a highly specialized processors, will not be able to do everything efficiently. That’s why satellite co-processors will appear around the DSP, responsible for the “smart” camera functions, from autofocus to computational imaging. But this is complete speculation on my part. And of course, we should not forget about the global microprocessor crisis, which certainly affects camera manufacturers as well.

24-volt power supply and B-mount will become standard at the high end

More sensitive sensors, more powerful processors — all this will require an increase in the power consumption of a cine camera. In the coming years, we are going to see a gradual move towards 24-volt power as standard. 24 volts has a lot of advantages: it is more efficient, it allows more current to flow through the same thickness of wire, producing less heat and losing less voltage over significant lengths of wire. For cameras, this means a major upgrade in terms of power consumption without a significant increase in the thermal budget.

B-mount slides from the side, same as Gold mount. But the locking mechanism is located in the battery pack rather than the plate, which makes one-handed battery swaps easier. Also, notice the extra pins ins the mount for data battery transfer.

ARRI has already announced that their next Super35 4K camera will run exclusively on 24 volts and will feature a native B-mount, ARRI’s new battery mount. Fortunately, B-mount is an open spec, and many manufacturers (SWIT, Bebob, Core and others) have already introduced an ecosystem of batteries, chargers and battery plates. Another benefit of the B-mount is its advanced protocol for “talking” to the camera, which traditional V-mount and Gold-mount lack. This allows for more precise voltage regulation and much more battery health data to be communicated to the camera. In short, batteries will become “smart” and yeah, productions will have to upgrade their whole battery fleet.

More cubes, yay!

This might very well be the next cinecam from Canon. The image is from a recent patent filing in Indonesia and could depict the rumored EOS C50. The similarity with RED Komodo is striking.

I’m a big fan of modular design. A cube-shaped camera allows you to configure the rig for the task at hand, whether it be a tripod, shoulder rig, gimbal, drone, crane or whatever. Ergonomics are also quite important for a camera, and the modular design provides room for customization. And on a more personal level, all this tinkering allows the operator to express themselves in some small way through their “perfect rig”. I know I do.

I bet more mainstream manufacturers will give the cube form factor a try in the coming years. But modular design is not without its problems. First, it obfuscates the true cost of the camera. Yes, the RED Komodo costs $6,000, but to turn it into a workable camera you’re going to spend another $2,000–4,000, depending on the options. And RED, oh, how they love to overcharge tenfold for every little wire and adapter.

The second issue is the ecosystem (or lack thereof) around the camera. What is the point of modular design if there are no modules to choose from? For the ecosystem to be commercially justified, there must be some degree of compatibility and continuity between the generations of cameras, like ARRI (Mini => Mini LF). In this regard, I must give props to Kinefinity — the Chinese manufacturer has established a great selection of accessories and modules for their Mavo cameras. Sony and Canon, on the other hand, are still lagging behind in this regard: each new camera is a new form factor. Some of their offerings are vaguely cube-shaped, but not truly modular. The Japanese are conservative, but sooner or later they still react to the trends, so let’s wait for more cubes!

The software is the next battleground

I can hardly be called an apologist for smartphone video. It looks like crap and does not pose any threat to professional cameras, simply because of the laws of physics. But this does not mean at all that cameras are better than smartphones in every way. Gadget manufacturers have learned how to use computational methods to mask and overcome the shortcomings of tiny sensors. Smartphones can glue together best parts of multiple exposures in real time, identify faces and objects, create depth maps, apply AR effects, embed 3D objects in space — all this in addition to autofocus and stabilization, which oftentimes outperform dedicated video cameras.

I’m not saying we need AR masks and fake depth of field in our cameras. But what about, for example, being able to fix a focus miss in post? Or recreate the information lost in the highlight? More sensors are appearing in cameras — lidars, gyroscopes and accelerometers are already being integrated by progressive manufacturers (DJI Ronin 4D). Data from these sensors will help power the next generation of autofocus and stabilization systems. I believe that all these “smart” functions will first appear in the mirrorless segment. But even elite manufacturers should start considering upgrading not only the hardware, but also the software of their cameras.

Remote controlling the camera will become easier

UI and UX is another area in which cameras should learn from smartphones. Camera interfaces just plain suck. They are slow, they are unintuitive, they are ugly, the text is too small, the menus are too long, there are too many settings (I speak as a person who loves settings). This is true to varying degrees for all brands. Of the modern cameras, only BMPCC has a decent interface. Albeit the camera’s ergonomics had to be sacrificed for that, but the touchscreen interface is the right idea.

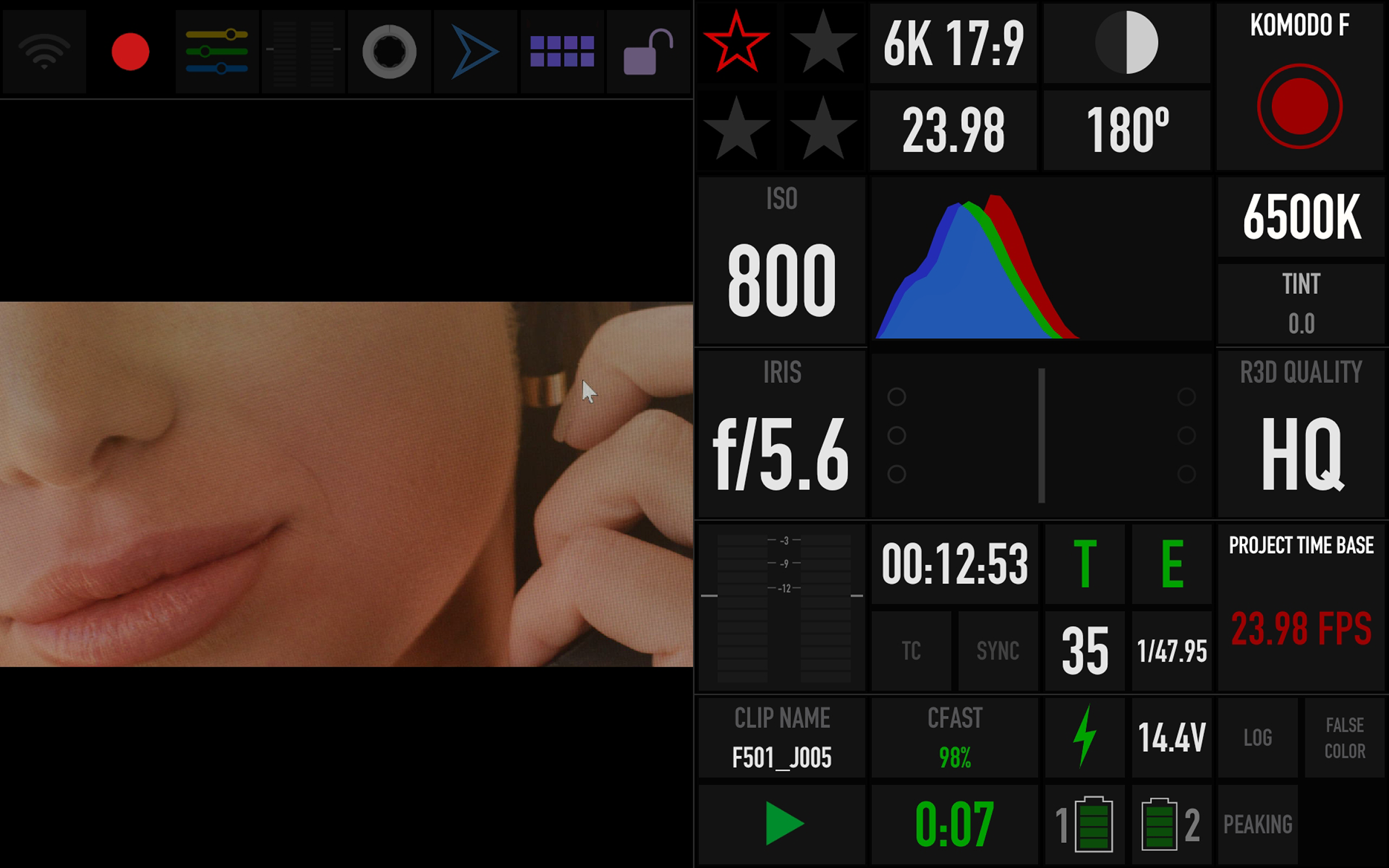

The problem is that on modern cinema cameras there is less and less space available for the screen and buttons, because the cameras are becoming smaller and cube-like. And when the camera is fitted on a crane, a cable or on a drone in the sky, remote control becomes the only option. And way too few manufacturers provide robust solutions for that.

RED has set a high bar in terms of camera control apps. Other manufacturers should take notice.

Every time I use the Sidus Link app to control Aputure lights, I think “why is this not available for my camera”? Only RED and, oddly enough, Z Cam have full-fledged applications as of right now. Sony and Canon urgently need to come to their senses and release modern apps that give full control over all camera functions. If the “cube” trend continues, only the primary controls will remain on the camera body, and the main menu will be gradually pushed out into the smartphone application. And those have to get better.

Wireless monitoring and broadcasting will be integrated

A decent camera control app is impossible without a stable wireless signal transmission from the camera, otherwise the whole point is lost. Today, 5 GHz transmitters have become so small that they can even be integrated into “cubes”. Of course, this does not eliminate the need for external solutions if signal transmission over long distances or in difficult conditions is required. But at the very least the camera should provide the operator and the focus puller with wireless monitoring, since the distances are usually small and the line of sight is unobstructed.

Another thing that is trivial for a smartphone, but missing from a camera is RTMP broadcasting. Perhaps adding a SIM card and an antenna to the camera to connect to LTE / 5G networks is prevented by some kind of regulatory certification. But at least streaming via a smartphone (again, via the camera app) should be a standard feature of a modern video camera. All this is of course possible today through various third-party solutions, but camera manufacturers should really integrate this functionality natively and take this opportunity to make it more seamless and elegant. Like a smartphone.

32-bit float audio will be built into cameras

32-bit audio is divine. This is one of those features that makes the life of a working professional easier without creating additional problems for them. For those who are not in the know, 32-bit float is an audio recording format with a huge dynamic range that “floats” to accommodate even great changes in signal level. In practice this means two things: 1) audio is almost impossible to clip and 2) vice versa, even the quietest signal can be raised in post without significant increase in noise. In other words, this feature eliminates the need to control recording levels while shooting.

I see no reason why this can’t be integrated into a camera.

To be honest, I wonder why this is still not in our video cameras. Judging by the tiny 32-bit recorders that have come out lately (for example, ZOOM F2), this technology does not require either tons of processing power or meaningfully more memory (compared to video files, a 33% increase in audio files is immaterial). Also, I am not aware of any patent and licensing restrictions that would prevent the implementation of this technology in cameras. Especially in cameras aimed at solo operators such as Sony’s PXW line or Canon’s Cinema EOS line.